Posted by Alliance of Indian Wastepickers

Written by Kabir Arora

Region Asia-Pacific

Country India

October 06, 2015

Written by Kabir Arora. Waste Narratives. 10/05/2015

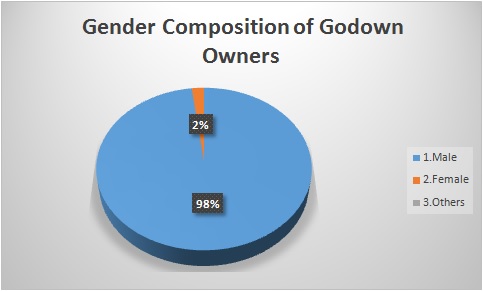

Gender Composition

Notes from Nayandahalli

Historians have always been interested in cities and their resource inflows. They rarely ventured out from their comfort zones and talked about outflows. Romila Thapar‚Äôs book ‚ÄėAsoka and the Decline of the Mauryas‚Äô sheds a lot of light on Mauryan capital. We all know that Pataliputra, the cosmopolitan capital of Mauryan Empire, was sourcing cotton from some such and such area; wood was being sourced from geographies varying from lower Himalayas to Kalinga in South. What do we know about its waste management, except the names of certain castes and social groups who were responsible for it? Same goes for Mughal era cities. Neither waste nor waste workers were fancy enough for historians to study and write about. Let us look at the books on Bangalore. Janaki Nair‚Äôs masterpiece, ‚ÄúThe Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore‚Äôs Twentieth Century‚ÄĚ, ‚ÄúBangalore‚ÄĚ by Peter Colaco are all but silent about waste economy and management. Let us accept that waste has never been so interesting to be written about. City historians have been silent about its existence.

Not one of us in Hasiru Dala knew how to write, leave aside writing description of the city. We undertook the challenge. We are an association of waste workers, we want to tell the story of Bangalore, and through the waste it generates and manages. We want to tell our stories in our own way. We chose Nayandahalli as our laboratory.

How do you describe a city?¬† Is there are particular style to follow? Give some statistics, share some anecdotes and move on to sermons about what is wrong with the city, romanticise its elements and add some masala of ethnographic divisions. Not so sure! There are books written about cities, their past, present and future. There is no single recipe to formulate understanding of a complex creature or an ecosystem called ‚Äėcity‚Äô. Notes from Nayandahalli is our way of looking at Bangalore, ‚Äď the fifth metropolitan of India, through its waste and the eyes of waste workers.

A lot has been described about Nayandahalli in our previous posts. A lot more is to be shared.

Nayandahalli is a settlement of urban nomads, whose existence and movement is dependent on land and petroleum prices. These urban nomads are sorters, godown owners and factory wallas. I will use the term ‚Äėrecyclers‚Äô for them in this post, as it is all encompassing. They buy waste from all over the city through scrap dealers and wastepickers. Bring it to Nayandahalli. Sort it in varying categories; transport it to factories in vicinity, where waste is processed. After processing, the waste which became raw material is forwarded to manufacturing units. They use it for producing finished products. To conclude, it is in Nayandahalli that the waste becomes a resource- raw material for booming manufacturing sector.

Why do I call recyclers urban nomads?

Recyclers are constantly on move. Their movement and existence is dependent on petroleum and land prices. Most recyclers are tenants. Very few of them own the land on which their factories or godowns are constructed or installed. The moment land prices go up; their landlords give them the notice to leave. In past many godown owners were based in Gangondanahalli and Shyamanna Garden, from there they moved to Nayandahalli. The land prices in Nayandahalli are shooting up fast, thanks to the metro rail extension to the area. The recyclers have already received the notices. They will soon be packing their bags, dismantling the structures they have installed and leave for another place. Their constant displacement makes them nomads. They are angry and want to get rid of this forced nomadness.

Akmal Baig, leader of informal association of godown owners, asks pertinent question ‚ÄúWhy can‚Äôt government allocate us land on subsidized prices like they do for other industries and corporations to carry out our business? We want to be stationed at one place. We are happy to pay for the land in installments as we pay rent. It takes a lot of money to install a shed, and dismantling it is also an expensive affair. We are tired of moving.‚ÄĚ

Land prices displaces them, petroleum prices hit their stomachs fiercely. Whenever petroleum prices drop, dhanda becomesmanda. In the time of low petroleum prices, as it is now, manufacturing finished products with virgin raw material is cheaper than the recycled ones. Recycling units shut down. It forces many to move to other informal economy vocations. There are no guidelines suggesting industry to have certain proportion of recycled material in their products. Any such measure undertaken can stabilize the demand for recyclable material and reduce the harm caused by reduced petroleum prices.

Increased land prices, reduced petroleum prices induce nomadness. Continued here…

The post here is a part of the Notes from Nayandahalli series and is a reflection of an ongoing study supported by Indian Institute for Human Settlements and WIPRO Cares. You can find the previous posts here… Post 1, Post 2 and Post 3. The survey  is ongoing and is being conducted by Malleswari Baddela and R. Usha.

Tweet