By Deia de Brito

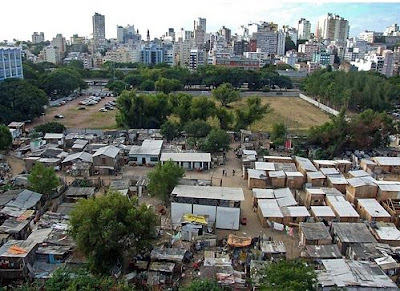

At an event organized by the National Movement of Waste Pickers in Brazil (MNCR) during the People’s Summit, speakers from different social movements and organizations spoke about the removal of street vendors, homeless populations and waste pickers. These forced removals are increasing in Brazil as the country becomes one of the world’s largest economies. Brazil is also joining the ranks of other growing nations; taking on mega-events such as the hosting of the 2014 World Cup Games and the 2016 Olympics.

The panel, held in MNCR’s event space at the People’s Summit, was called “Resisting the Hygienization of Urban Centers.” Maíra Vannuchi, a national campaign coordinator with StreetNet—an international federation of street vendors—spoke about the group’s fight against the “clean up” of urban centers. Vannuchi and other coordinators have been working to organize street vendors in other host cities before the World Cup and the Olympics. In South Africa and India—where the World Cup and Commonwealth Games were hosted in 2010—the removal of street vendors and other street populations was “like a tractor taking everyone out,” Vannuchi said.

Since 2006 the StreetNet campaign, called “World Class Cities for All,” has focused on speaking up for organizations to prevent that kind of government and corporate disregard for informal workers. The organization began the campaign in Brazil in 2010. Part of its work includes hosting political information courses with street vendors in 7 of the 12 host cities across Brazil. It has also joined forces with local organizations and social movements; as well as participated in the Comitê Popular da Copa: a committee of social movements, NGOs, academic institutions, leaders, and community members. The Comitê Popular da Copa meets regularly to discuss its goals, which include mobilizing against policies that exclude informal workers and pushing for democratic discussions about organizing mega-events fairly. “Repression and the will to eliminate anything that is a reminder of poverty in the cities leads to the disappearance of street vendors and other vulnerable populations,” Vannuchi said.

One of StreetNet’s projects was a mapping of street vendors in Brazil’s host cities. In 2009, when the Rio city government began requiring that street vendors obtain licenses to work, it made licenses available to less than one-third of the vendors. That left an estimated 40,000 without licenses. They now run the risk of having their livelihoods taken away if they are caught working on the street.

“The process of licensing the street vendors was actually a mechanism of ‘cleaning up’ the city,” said Angela Rissi, a leader with Associação dos Expositores Das Feirartes e Outros (AEFO), an association of artisans and other street vendors.

As major cities focus on “beautification,” “revitalization” and other forms of attracting business and investment, activists from the affected populations are coming together with common demands. In January 2012, the community known as Pinheirinho—in São José dos Campos, São Paulo—was violently evicted. The community had been living in the area for eight years. This was allowed by Brazilian law; the law says that land that is not serving a social function can be used for housing. The land where the Pinheirinho community belonged to a bankrupt company—Selecta.

Military police and municipal guards evicted between 3,000 and 9,000 families from Pinheirinho. There were numerous reports of human rights violations on the part of military police and city employees; including excessive violence, psychological pressure, lack of services for children and the elderly, and the confiscation of possessions. Many residents were hospitalized; some even disappeared.

Of course, among those evicted were many waste pickers. Twelve members of the Cooperativa Futura, one of MNCR’s bases, lived in the community. Another 300 waste pickers were residents of the community and worked at an association there. After the removal of the Pinheirinho community residents ended up in the streets, at homeless shelters, with relatives, and buying tickets back to the cities and towns they migrated from.

Across Brazil, an estimated 200,000 people are threatened with eviction because of urban “clean up” efforts related to the World Cup and Olympic games. That’s why it’s important that communities, workers and social movements come together to demand their rights.

Members of the Brazilian waste pickers’ movement have been meeting with street vendors since 2010; when StreetNet hosted a seminar in Senegal. Leaders from various movements met with street vendors and waste pickers there, said Madalena Duarte, a national coordinator with MNCR. At the end of the seminar, participants drafted and signed a letter in support of African street vendors. In 2011, another letter was drafted in São Paulo, whose aim was to protect street vendors and other populations in the lead up to the World Cup in Brazil.

“Many low-income communities have been removed in Brazil,” Duarte said. “Street vendors, waste pickers, street dwellers, and favela residents are suffering because of World Cup revitalization.”

“Street vendors and waste pickers both use public space to survive —the street is a place of livelihood for the most socially vulnerable populations,” Vannuchi said. “For the StreetNet movement, the Brazilian movement is a great inspiration—every time I talk to street vendors, I talk about waste pickers.”

Angela Rissi, with AEFO (Associação dos Expositores Das Feirartes e Outros), described her admiration for the Brazilian waste pickers’ victory in achieving the National Waste Policy, made law in 2010. Street vendors are hoping for a future federal policy that will provide social security for informal workers; protect informal workers from being violently removed and having their goods taken away; and provide fair licensing requirements. But first, the street vendors are working to gain recognition as real workers. In Brazil, waste pickers received this recognition in 2003 when the category was included in the National Workers’ Policy.

Regardless of the success, when cities decide to clean up urban centers, street vendors and waste pickers are among the first categories of workers to be displaced.

Tank Menezes, with the National Movement of Waste Pickers in Brazil, provided some devastating examples from his own city. In Porto Alegre, a downtown community known as Chocolatão—or the Big Chocolate—had existed for more than 20 years. It was made up of about 250 families and about 700 people. Most of the community earned their living as waste pickers; recycling what was produced by the neighboring federal justice building and the rest of downtown.

In 2011, as part of the city government’s World Cup clean up efforts, it evicted and relocated the community to a part of the city 10 kilometers away—all the way to the border of the next city; about an hour and a half by bus. The waste pickers who worked with pushcarts were not allowed to take them to their new homes.

Menezes said that this “revitalization”—a term used by the city government—has been an ongoing process over the past two decades, removing poor communities from the downtown area with the goal of turning the city into a tourist destination.

“The officials talk about how the new apartments are so pretty; but the fact is now everyone is out of work,” Menezes said. “It didn’t bring any dignity because the community was taken from their place of work. They don’t know where to find the recyclable materials. They don’t know where to receive assistance, or find a health clinic, either.”

While the Chocolatão community lacked infrastructure, the residents were located near plenty of downtown services. As part of its agreement with the community, the city built a recycling warehouse in the new neighborhood. Only 30 or 40 of the nearly 700 residents who worked as waste pickers had an opportunity to work in the new warehouse, which allowed only a certain number of workers to work there. In addition, the “model” recycling center is too small, lacks the right amount and type of equipment and is plagued by bad design, and poor insulation, so it gets very cold in the winter and hot in the summer.

Since the majority of the community survives as waste pickers and they have been unable to find work in the new location, many leave their apartments in order to work downtown. During that time, they sleep on the street.

“It’s an extremely violent repression without any negotiation,” said Vannuchi. “To make this World Cup, they have to remove the poor. They don’t talk with the communities or social movements. In this process of urban removal, everyone is affected.”

Maria do Carmo Santos, street vendor representative (right) with Nohra Wintour (middle), Streetnet, and another street vendor. (credit: Maíra Vannuchi)

“This global perspective is extremely important to know,” said Carlos Alencastro, a national leader with the Brazilian movement. “Working together we can have the strength to fight this problem. Today many people talk about urban reform. We can’t talk about this anymore without getting involved and finding a solution.”

“Waste pickers are suffering the same problems as the street vendors and street dwellers,” said Madalena Duarte. “It’s important that our fight becomes one, despite our differences.”

Tião Rocha, an audience member, said, “I think Rio+20 starts and ends with this issue. Human rights were never respected in this country. Twenty-four years of dictatorship ruined this country. Hygienization is the opposite of humanity.”

“They are treating street populations as if they were trash,” said Maria do Carmo Santos, a street vendor and activist with the Street Vendors United Movement (MUCA). “We have no health care, no education and we are forced off the streets. We are only allowed into the city to wash rich women’s underwear. We have no place in the city.”

Tweet

there are the same problems all over the world.

Comment by krishnarjun — September 27, 2012 @ 10:18 am